The Design Brief® | Volume XXIV | Common Code Pitfalls Designers Make that Cause Contractors to Cringe

©️ Dakota Design Company 2017-2026 | All rights reserved. This content may not be reproduced, distributed, or used without permission.

WRITTEN BY DR. GLORIA for DAKOTA DESIGN COMPANY

Why Interior Designers NEED to Know the Residential Codes

It is critical that designers who are producing residential floor plans understand the relevant code requirements. Codes are the law, and the requirements must be followed.

Most often, if a designer draws a floor plan or lighting plan that misses code compliance, the licensed plumber or electrician, or the experienced carpenter or installer will recognize the deficiency, and make a correction on site or during installation. Within their specialty, good contractors are well aware of the requirements and keep up on any code requirement changes. Or, during a plan review for a building permit application, a code deficiency might get tagged for revision. And, even if something is installed or constructed incorrectly, a building inspector should catch it during an inspection (but then, of course, there may be a hefty cost to the homeowner to reconstruct the element per code requirements!!!)

This is all very comforting to designers. Mistakes and improper applications get caught and fixed along the way during plan reviews and construction. So, the real risk when a designer is ignorant of the codes is that they lose credibility with contractors and installers. AND, that gives the entire industry a bad name.

Can you almost SEE the contractor rolling their eyes when they see a designer’s plan that has missed a basic requirement???

Can you almost HEAR the men on the job site chuckle over the silly designer’s scheme that misses the mark with plumbing, electrical, or life safety codes?

Yeah, right. This is why some designers get a bad rap.

And this is also why we at Dakota Design Company have developed the Residential Codes Handbook, which includes summaries and diagrams of ALL codes related to single-family homes. Additionally, we update it every three years when the International Residential Code (IRC) and the National Electrical Code (NEC) are revised, and we send all purchasers an update to keep them informed about any code changes.

But in this post, we will cover the key areas where designers might miss the mark when it comes to code compliance.

How Can Designers Access the Information in the International Residential Code, and Other Pertinent Code Documents??

The International Codes Council, which writes and publishes new Code editions every three years, provides online access to the Code documents, so you can check it at any time in regards to requirements for specific building elements. Even if you have never read a codes document, I encourage you to go to this link to check out the 2024 version of the IRC. Go ahead. It is not as daunting as you may fear. Yes, it is written in legalese, but it is neatly organized per chapter and sub-chapter, so it is fairly easy to navigate to the section that may answer a specific question. And, every three years when updates are made and a new code edition is published, anything that has been revised is written in blue (rather than black) font, so it is easy to identify new requirements.

Much of what is of interest to interior designers for space planning purposes is covered in IRC Chapter 3, Building Planning.

Unlike the free access version of the IRC, unfortunately, the National Fire Protection Association which publishes the National Electrical Code (NEC, or NFPA-70) does not likewise make this publication available for free online. The NEC is the document, also updated every three years, that includes all requirements for outlets, switches, and light fixtures, so it is very important to interior designers. Only by purchasing online access or a print copy can one gain access to this code.

So, if you don’t want to READ the IRC, or if you do want to stay informed about changes to the electrical codes, remember that we do it for you, so you don’t have to!

Door Code Pitfalls

There are few requirements in the codes for doors in single-family homes, but the ones that exist are outlined in Chapter 3, Section 318: Means of Egress. That is because the codes are not so much concerned with interior doors between rooms. What they ARE concerned with is that, in the event of an emergency, people can easily exit the home through a main door leading to the outdoors. That is typically the door that also serves as the home's main entrance — or, the front door. This is considered the main egress point of the home.

That main entrance/exit door needs to have a clear opening width — when the door is opened 90 degrees — of 32”, and a clear opening height of 78”. This gives ample room for anyone to exit through it. Because, in an open position, the door leaf itself, as well as the door stop, reduces the clear opening width; a 36” wide door is typically used. And, there is a door stop at the top of the door frame, so an 80” high door is used to allow the required 78” clear height.

So, the minimum door size that should be specified for a front entrance door of a home is 36” wide x 80” high or higher.

The same code section IRC 318.2 also requires that the main entrance/exit door, typically the front door, be side-hinged. There is no requirement for whether the door swings inwards or outwards; either are possible.

Pivoting doors, such as the one shown below, do not meet the letter of the code, in that they are not side-hinged, so their use may require permission from the code official in the jurisdiction, and substantiation that the clear width when in the open position will be a minimum of 32” wide and 78” high, and that the door is easily openable from the inside.

The intention is that it is easy to exit the main door of the home if needed. Regarding this main door, the IRC states, “Egress doors shall be readily openable from inside the dwelling unit without the use of a key or special knowledge or effort” (2024 IRC, Section 318.2).

If there is to be a step or steps, either up or down, immediately inside the main door (the door considered to be the egress door), the landing must be as wide as the door itself, and must be at least 36” deep (in the direction of travel).

The IRC does not address requirements for interior doors, as they do not serve as the primary egress point of the home; however, interior doors are manufactured in standard sizes. Standard door heights for interior residential doors are 6’-8” (80”), but are also made in 7’ heights (84”) and 8’ heights (96”) for use in rooms with higher ceilings.

Standard residential door widths are manufactured in 2” increments, such as 2’-2”, 2’-4”, and 2’-6” wide. Standard usage is 2’-6” wide doors used at bedrooms, and 2’-4” doors at bathrooms.

Stairway Code Pitfalls

Within the IRC, the requirements for stairways are outlined in Section R318.7 of the Means of Egress section. The intention is that, if a resident needed to exit quickly in an emergency, the stairway would be easy to navigate. However, these requirements also ensure that all elements of a stairway are easily manageable day in and day out.

A stairway in a residential building needs to be 36” wide and have a handrail traversing the entire height or the stairway on one side. That handrail can protrude into that 36” required width up to 4.5” (leaving a clear width at the railing of 31.5”). Stairways leading to nonhabitable attics do not have these same requirements.

For residential stairways, the maximum riser height is 7¾” high (for commercial buildings, it is 7”). The minimum tread depth for a stair tread is 10” (the tread depth requirement for commercial buildings is 11”). If there is no nosing, the tread depth needs to be 11”.

The reason for the difference in tread depth requirements with or without nosing is that a person’s foot has more space when climbing the stairs, allowing the space under the nosing to be utilized, compared to descending the stairs, when the space under the nosing cannot be utilized.

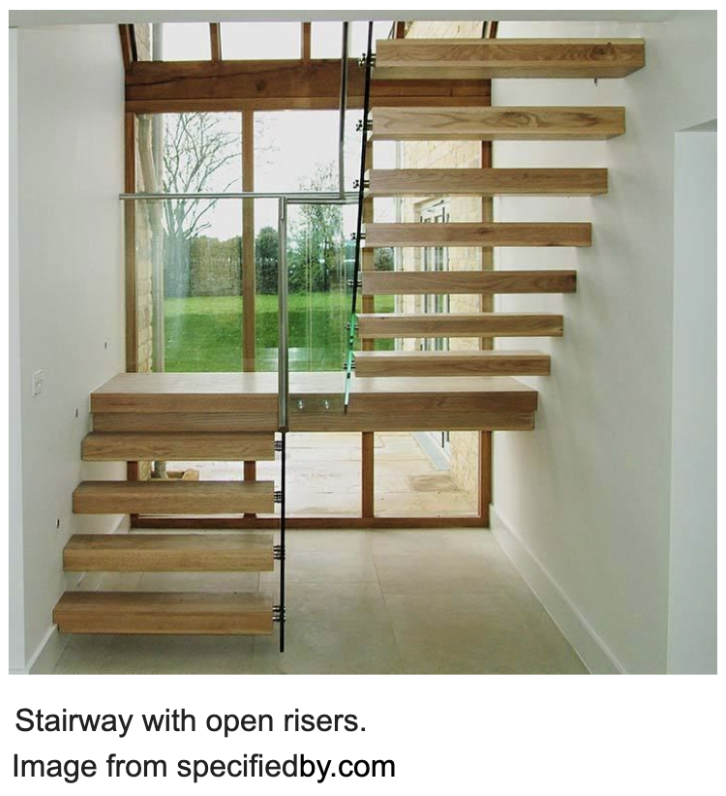

A stairway with open risers is allowed, provided that — for the stairs that are more than 30” above the floor below — the opening cannot allow a 4” sphere to pass through. That ensures that a small child cannot pass through that open riser and fall.

Spiral and winder stairs are allowed, and have different requirements. For spiral stairs, the clear width must be at least 26”. Each tread must have a depth of at least 6.75” at the walkline. The walkline is the path 12” from the inside side of the stairway — literally where you walk while holding on to the handrail.

With spiral stairs, all the treads need to be identical to one another, and the rise between each tread cannot be more than 9.5”. Headroom for a spiral stair must be at least 6’-6”.

Winder stairs are those where the tread shape is trapezoidal, where the step edges are not parallel to one another. Some stairways include a mix of standard steps a winder steps, as shown below. Winder treads must be 6” deep at their narrowest point, and 10” deep at the walkline, which is 12” from the inside of the turn.

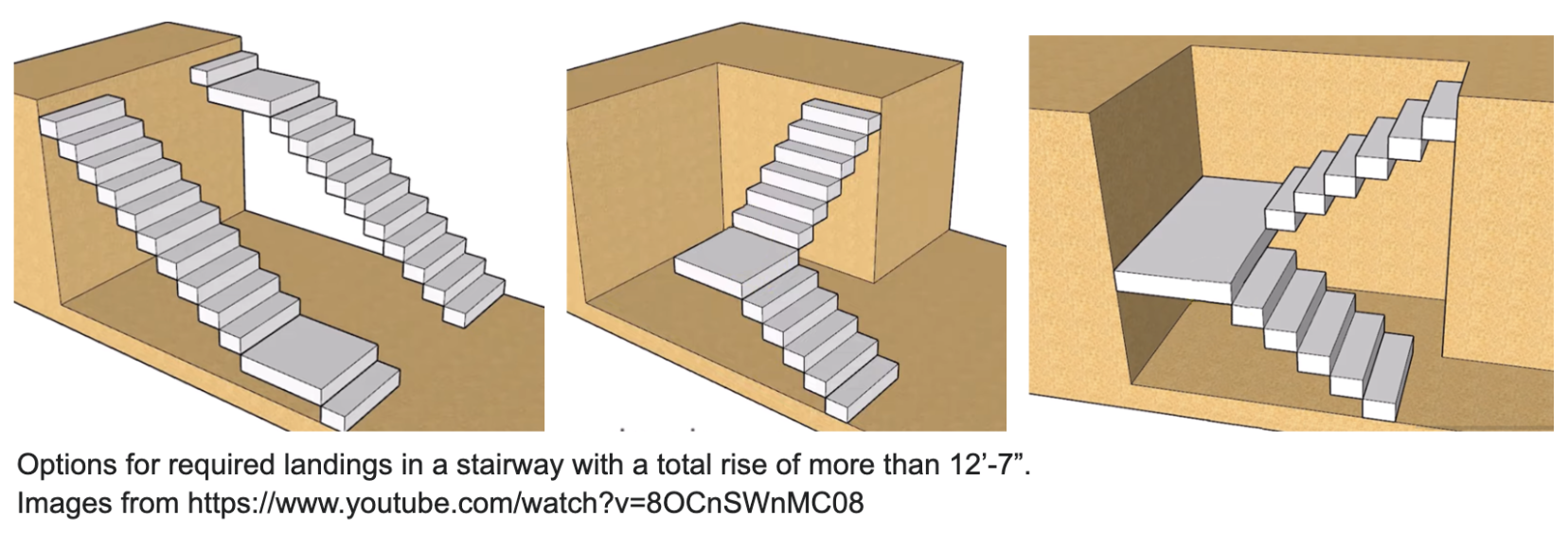

If the floor-to-floor height between two different levels in a home exceeds 12’-7”, the stairway connecting those two levels must include a landing. That landing can be located anywhere along a straight-line stairway, or along a L-shaped or U-shaped (switchback) stairway.

The landing must be at least as wide as the stairs themselves (minimum 36”) and at least 36” deep, but can certainly be larger.

Kitchen Code Pitfalls

Designers are most likely to overlook code requirements for kitchens regarding electrical outlet placement, if they are providing a lighting/electrical plan.

In kitchens, wall outlets above a countertop should be placed so that no point along the wall behind the countertop is more than 2’ from an outlet. In general, this means that there should be an outlet at least every 4’ apart. Wherever there is a countertop section 12” or wider, a wall outlet needs to be included on the wall behind.

A GFCI outlet has an internal sensor that functions like a circuit breaker to prevent electric shock. The flow of electricity is immediately halted if an unusual condition — such as the presence of water — is sensed.

With the most recent versions of the National Electrical Code, all receptacle outlets within kitchens are now required to be GFCI. Previously, only those within six feet of a kitchen sink, or above a countertop were required to be. So, the requirement depends on which version of the NEC — the most current, or a previous version — is being enforced in the jurisdiction. Also, any outlet within six feet of a washing machine or laundry sink must be a GFCI.

There was a significant change regarding requirements for outlets at kitchen islands and peninsulas within the 2023 NEC and the 2024 edition of the International Residential Code. Prior to that, it was required that an outlet be installed at the end of an island or peninsula of any size, no lower than 1’ below the countertop surface. And a larger island or peninsula may require two or more outlets.

This proved to be a risky solution, as pets or children passing by could catch a dangling electrical cord, and pull down a small appliance. So, these outlets at the sides of islands or peninsulas are no longer allowed (this is true for new construction or remodels; existing conditions are always grandfathered in). So the current requirement for power within islands and peninsulas in new construction or remodels can be one of three solutions:

1. A receptacle outlet installed above the countertop surface (not more than 20” above).

2. Use of a receptacle outlet assembly designed specifically for countertops.

3. Electrical wiring be provided somewhere in the island or peninsula so that a receptacle outlet can be added at a later date.

Bathroom Code Pitfalls

Within the IRC and National Electrical Code, there are also very specific requirements regarding bathrooms, and locations for outlets and light fixtures.

Every bathroom must have at least one electrical outlet. It should be at least 1’ away from the edge of the sink, but must be within 3’ of the edge of the sink, and it needs to be a GFCI. If the bathroom has two sinks, each must have an electrical receptacle within 3’. This may mean placing the outlet between sinks or installing two separate outlets.

A bathroom must have one wall-mounted switch by the bathroom entrance that operates a light. In most parts of the country, either an operable window or an electric vent fan that exhausts moisture from the room is required.

One area where I see designers making errors within bathrooms is specifying a chandelier or pendant fixture to hang above a bathtub. This is not allowed, unless the ceiling is particularly high so that the fixture can be hung well above the bathtub.

No light fixture (or part of a light fixture) — such as a pendant, ceiling fan, chandelier, or track lighting fixture — unless it has been UL approved for wet or damp locations, can be within an area measured 3’ horizontally, and 8’ vertically from the upper edge of a tub or the threshold of a shower. Similarly, an electrical outlet cannot be placed in this zone. The image below illustrates this restricted zone that is above or within 3’ horizontally, and 8’ vertically of a shower threshold or tub edge.

It is possible to stay well-informed about the codes that affect interior design practice and about code changes as they evolve. But if that is not an additional responsibility you want to undertake, please let us help you with your codes knowledge. You never want to be perceived as uninformed about these critical requirements.

Source used:

International Code Council. (2024). 2024 International Residential Code. ICC Publications.

Kennon, K. E., & Harmon, S. K. (2022). The Codes Guidebook for Interiors, 8th ed. Wiley.

National Fire Protection Association. (2023). NFPA 70 National Electrical Code. NFPA.

Want The Design Brief® delivered straight to your inbox?

If you liked this email, be sure to sign up for The Design Brief®, our complimentary publication that gives you bite-sized lessons on all the technical interior design topics you didn’t learn (or forgot) from design school—straight from our resident tenured interior design professor!

Looking for more? Keep reading: