The Design Brief® | Volume XXVII | Why Visualization Skills Are So Important to Interior Designers

©️ Dakota Design Company 2017-2026 | All rights reserved. This content may not be reproduced, distributed, or used without permission.

WRITTEN BY DR. GLORIA for DAKOTA DESIGN COMPANY

This post is about a topic I have been thoroughly fascinated with for the last several years—ever since I became aware of this topic’s existence. A few years ago, I read an article in The New York Times that left me astounded. How did I not know about this phenomenon, so closely tied to a creative professional’s abilities?

The illuminating phenomenon I am talking about is the ability, or in some cases, the inability to willfully bring an image of something into your mind’s eye—to see something in your head. I had never given this any thought at all, but have come to understand that I have a very agile mind’s eye, and that this ability has served me well over my career as an interior designer. And, I understand that many people are not able to conjure images in their mind’s eye at all! How many times have we designers had clients wring their hands and become paralyzed with indecision, and say, “OOOOH, I just don’t know. I just can’t see it!!!”? (I have often clients that I CAN see it, and they need to trust me.)

What is a Mind’s Eye?

Imagine being asked to close your eyes and picture a friend's face, or visualize a sunny beach. For most people, that mental image appears easily and vividly, like watching television. But for others, that internal visual screen does not exist. They can recognize what the friend or the beach looks like and describe it verbally, but they cannot see those images in their minds.

A mind’s eye could be described as a mental camera, or the ability to visualize in your imagination. People with a dexterous mind’s eye are able to rely on visual images they see in their mind for a variety of purposes, for instance, to navigate a traffic route by seeing a map to the destination in their head.

The Times article I read back in 2020 actually described the opposite of this skill—the inability to conjure an image at will in one’s mind. One person described being perplexed when, as a child, she was instructed to count sheep to help her fall asleep. The notion is that the repetition of the mundane image of continual sheep jumping over a fence will be so boring that it will put you to sleep. But she couldn’t see anything at all in her mind’s eye, just blackness. She also described being told to visualize the characters while studying Chinese in college, but she couldn’t imagine how to possibly do that. Another person described his inability to conjure images as “thinking only in radio.” A certain percentage of the population experiences the world without pictorial mental images.

In 2010, the inability to recall a chosen visual image in one’s mind was given a label—aphantasia, or having a blind imagination. And the opposite ability—being able to readily form mental visual images of anything—was labeled hyperphantasia. Now that I better understand the mind’s eye phenomenon, I realize I am hyperphantasic. And I also realize that it is a valuable skill for an interior designer.

When Were Mind’s Eye Skills First Recognized?

The earliest empirical research on the mind’s eye phenomenon—or visual imagery skills—was conducted in the late 19th century by Sir Francis Galton, who asked study participants to visualize their own breakfast plate from earlier that morning. He found that some people had absolutely no ability to recall that visual image, even though they could accurately list the food items they had consumed.

How Do I Know Where I Fall on the Visual Imagery Continuum?

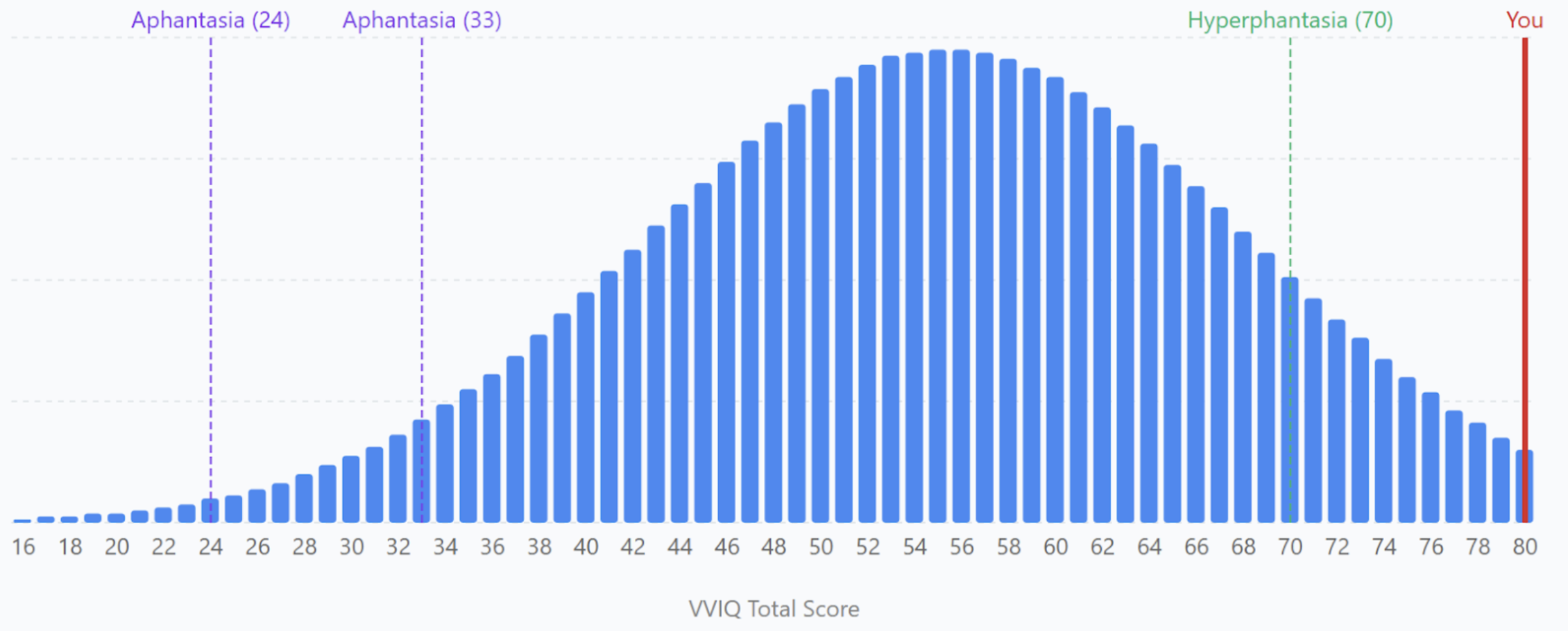

After Galton’s kitchen table study, interest in this phenomenon seemed to disappear for about a century, until the 1970s, when another researcher developed a questionnaire to quantify a person’s visual imagery skills by prompting them to conjure images of familiar things, such as a friend's face or the rising sun on the horizon. This Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ) is available on https://aphantasia.com/study/vviq. You can complete the questionnaire for free and receive your score immediately.

There are 16 prompts that have you conjure very specific images. A score of 16 means you are completely unable to see anything in your mind’s eye. You have answered that you can see “No image at all, I only know I am thinking of the object” to all 16 prompts.

A score of 80—answering “Perfectly clear and as vivid as normal vision” to the prompts—indicates hyperphantasia, or an unusually sharp ability to conjure mental imagery in your mind’s eye. (I scored 80 several years ago when I completed the questionnaire). It turns out that abilities follow a bell curve, with most of the population falling somewhere between 50 and 60. Different researchers define aphantasia, or having limited visual imagery skills, as a score of either less than 24, or less than 33. A score above 70 indicates hyperphantasia, or having very strong visual imagery skills.

One study found that nearly 9% of people describe themselves as being aphantasic, but less than 2% actually score as aphantasic on the questionnaire. This could mean that people have better visual imagery skills than they imagine, or that the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ) simply isn’t a highly valid or reliable test of mind’s eye skills.

Keep in mind also that at the middle of the bell curve, where the majority of people fall, people may have reported seeing only a vague, dim, or moderately clear image of the prompt. Being in the middle of the bell curve, as most people are, means one has some powers of visualization and visual manipulation, but not highly agile or vivid abilities.

What Does All of This Mean to Designers?

I have always been aware that I could see things in my mind’s eye, but I never gave it any thought until I became aware of this phenomenon a few years ago. I just assumed everyone had the same abilities as I did. But now I know that my abilities are not shared. I can completely rework a floor plan in my mind, seeing the walls, doors, and furniture move into place until the optimum arrangement is achieved. I often work out a plan in my mind, not sitting at my computer or looking at a plan on paper. I understand now that this is a unique ability.

I can also see exactly what a room will look like with a design scheme implemented, even if that means everything will change (location of elements, different colors and materials, new elements added). This is typically a fleeting image, like a camera flash. I don’t need to close my eyes. I just see it momentarily in my mind’s eye, but vividly enough to make judgment calls about the scheme, like that the proposed color might be too dark, or that an art piece might be over-scaled. I can see the elements, the colors, and everything as clearly and vibrantly as if I were seeing it in reality. And, later, when I see a completed space, it is very close to how I saw it in my mind’s eye. I am very rarely surprised.

But, I have very often had the experience of clients saying to me that they cannot see the design I have just presented. I was always perplexed by this. Just imagine it! I thought. And, over my 15 years of teaching, I have come to understand that some interior design students really struggle with seeing design options. A typical scenario is that I am looking over a student’s shoulder as they are working on a floor plan in AutoCAD. The configuration is not working well. I say to the student, “Oh, but if you flip the stairs, move the door, shift the cabinet, and rotate the sofa, voila! It will work fine!!!” When they look at me as if I am speaking Japanese, I know they cannot see those changes evolving from their drawn plan as I can.

As I have thought about visual imagery skills, and recognized that mine are quite sharp, I have thought about related concepts. I am not very musical, and do not have auditory imagery skills. If asked to hear a familiar song play in my mind’s ear, I typically cannot do that, unless the song is extremely well-known to me. I recently went to a piano concert where the pianist asked the audience to yell out their favorite songs, she wrote the titles down on a tablet, then sat down at the piano and played (by ear) all the songs in a medley. How could she do that?!?!? Well, she could hear the songs in her very agile mind’s ear, and she knew what keys to play to re-create what she heard. A composer can hear a melody in their mind’s ear to create a musical composition

In this same way of having an exceptional mind’s ear, designers tend to have very powerful mind’s eyes. They can create spaces that others cannot possibly imagine or compose. This is the skill that sets us apart, and makes our skills valuable to others, and well worth paying for.

What Don’t We Know About Visual Imagery Skills?

A lot!! Research into these phenomena—the continuum between a blind mind’s eye (aphantasia) and a vivid mind’s eye (hyperphantasia)—has primarily occurred within the fields of neuroscience and cognitive psychology. A 2020 study reported that individuals with low visual imagery scores were less likely to be employed in art-related and design professions, and more likely to be employed in professions involving computers, math, life, physical, and social sciences. And researchers have found that those with strong visual imagery skills tend to be better at problem-solving, especially in visual and spatial tasks. But that is where the research into visual imagery and the design profession ends. No other research has been completed on the correlation between design skills and visual imagery.

My personal discovery of this topic occurred near the end of my academic career. I retired from full-time teaching in interior design shortly after receiving tenure, thus meeting the requirements for research and academic publication. But I wish I had had the opportunity to research visual imagery skills to determine whether stronger visual imagery skills correlate with success at the student or professional levels in our field. In other words, can mind’s eye measurements help predict academic or professional success in design?

The work of Interior designers relies heavily on one’s ability to readily formulate mental visual images. But the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ) only tests for recall of already familiar images: a friend’s face, the facade of an often-visited store. Designing interior spaces means that one must visualize in one’s mind’s eye what has not yet been experienced—how a space might look with specific colors, materials, lighting, furniture, finishes, or how a not-yet-built space might look—and to make judgments based on these imaginings. And they need to be skilled in visual imagery manipulation—what would a space look like if we moved, rotated, or eliminated an element? Interior designers need to be very powerful visualizers.

No researcher or cognitive scientist has yet determined a way to measure the ability to conjure mental images of what does not yet exist, what can only be imagined by a creative person. If anyone reading this post scores low on the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ), know that the skills required of us designers are a bit different, and there may not be a correlation between being able to see known images and being able to see what we can only imagine because it doesn’t yet exist.

Let’s Conduct Our Own Bit of Research!!!

There are likely individual differences in the ability to visualize but also manipulate images of an imagined space in one’s mind, as interior designers must do. But there may be some interesting commonalities as well. Although this won’t be highly scientific, I would love to hear from designers who read this post. In a future post, I will report back on what other designers have shared.

I am anxious to hear feedback on this really interesting phenomenon, so please do share!!! I will write another post after hearing from readers about their experiences. It should be VERY enlightening for all of us designers!

SOURCES USED:

Bernan, M. J., James, B. T., French, K., Haseltine, E., L., & Kleider-Offutt, H. M. (2023). Assessing aphantasia prevalence and the relation of self-reported imagery abilities and memory task performance. Consciousness and Cognition, 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2023.103548

Dawes, A. J., Keogh, R., Andrillon, T., & Pearson, J. (2020). A cognitive profile of multi-sensory imagery, memory and dreaming in aphantasia. Scientific reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65705-7

Faw, B. (2009). Conflicting intuitions may be based on differing abilities: Evidence from mental imaging research. Journal of consciousness studies, 16, 45-68.

Galton, F. (1880). Statistics of mental imagery, Mind, 5, 301-318.

Keogh, R. & Pearson, J. (2018). The blind mind: No sensory visual imagery in aphantasia. Cortex, 105, 53-60.

Marks, D. F. (1973). Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures. British journal of psychology, 64 (1), 17-24.

Marks, D. F. (n.d.) https://davidfmarks.com/2020/03/10/vividness-of-visual-imagery-questionnaire-vviq/

Pearson, J. (2019). The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery. Neuroscience. 20, 624-634.

Puang, S. (2020, July 15). Living with Aphantasia, the inability to make mental images. The New York Times.

Zeman, A., Milton, F., Della Sala, S., Dewar, M., Frayling, T., Gaddum, J., Hattersley, A., Heuerman-Williamson, B., Jones, K., MacKisack, M., & Winlove, C. (2020). Phantasia – The psychological significance of lifelong visual imagery vividness extremes. Cortex, 130, 426-440.

Zimmer, C. (2021, June 8). Many people have a vivid ‘mind’s eye,’ while others have none at all. The New York Times.

Want The Design Brief® delivered straight to your inbox?

If you liked this article, be sure to sign up for The Design Brief®, our complimentary publication that gives you bite-sized lessons on all the technical interior design topics you didn’t learn (or forgot) from design school—straight from our resident tenured interior design professor!

Looking for more? Keep reading: