The Design Brief® | Volume XIV | How Frank Lloyd Wright Influenced American Design and Architecture

©️ Dakota Design Company 2017-2025 | All rights reserved. This content may not be reproduced, distributed, or used without permission.

WRITTEN BY DR. GLORIA for DAKOTA DESIGN COMPANY

It could be argued that no single person has influenced American architecture and design more than Frank Lloyd Wright. You likely have some familiarity with his life and work. But you may not realize the extent to which his life was filled with controversy, eccentricity, scandalous love affairs and marriages, tragedy, family desertion, perilous debt, and financial ruin. He was hugely charismatic, also pompous, a narcissist, a curmudgeon, a control freak, a self-promoter, a manipulator, an adulterer, a home wrecker, and a genius.

Read on. His story is just too interesting not to delve into.

Wright was born in Wisconsin in 1867 and died April 9, 1959, at the age of 91, almost exactly 66 years to the day of the time of this blog publication. He had a long and storied career. I have previously written about his approach to making a building seem at one with its surroundings, by emulating the horizon line. He was a great lover of nature and wanted his buildings to be in harmony with the surrounding landscape.

Folklore around Wright’s upbringing includes the story that, when his mother was pregnant, she predicted that her child would grow up to be a great architect. To fulfill her premonition, she decorated his nursery with engravings of English cathedrals to encourage his ambition. She also bought young Frank a set of wooden building blocks that he later said influenced his understanding of shape and form.

Wright attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison, but did not graduate. At the age of 20, he moved to Chicago and found employment as an architectural draftsperson. Due to the 1871 Chicago fire several years earlier, there was a great deal of redevelopment and rebuilding happening there.

Wright was notoriously ambitious, so found his way to becoming an apprentice to the successful architect, Louis Sullivan. Sullivan even loaned Wright money to build a new home for himself and his new bride, Catherine Tobin. But Wright wasn’t loyal and started moonlighting to complete house designs for additional clients.

Despite the additional commissions, Wright was perpetually financially strapped—a situation that was typical throughout his life—and unable to repay Sullivan on the loan. Whether Sullivan fired Wright, or whether Wright quit in protest because Sulllivan prohibited Wright’s sideline work, is disputed. Either way, Wright was out of a job, so he began his own architectural practice.

Meanwhile, Wright and his wife Catherine (known as Kitty) were raising six children in the Oak Park, Illinois home partially funded by Louis Sullivan, and Wright was designing forward-thinking homes for local clients. One fortuitous client project Wright undertook led to an affair with the client’s wife, Mamah Bothwick Cheney. Wright and Cheney were not discreet about their relationship, which caused much scorn and disparagement among their neighbors and acquaintances—a huge scandal.

Eventually, Wright—abandoning his clients, his wife, and his six children—and Mamah—abandoning her husband and two children—ran off to Europe together. During their year in Europe, Mamah’s husband granted her a divorce, but Wright’s wife Kitty steadfastly refused to do so.

When the couple returned, Wright built a new home near Spring Green, Wisconsin, which he called Taliesin. Although Wright was married to three different women during his life, it has been speculated that his mistress, Mamah, was the great love of his life, and that this period with her brought him great joy.

Unfortunately, it ended tragically. In 1914, while Wright was out of town for a work project, a disgruntled and mentally deranged live-in employee set fire to the home, and viciously murdered Mamah, her two children, and four other workers with an axe while the fire burned. Although these appalling events were a crushing blow to Wright, he was rarely in his lifetime without a woman by his side, so when Kitty finally granted him a divorce, in 1922 he married his then-mistress, Miriam Noel.

Miriam had basically stalked and coerced Wright into having a relationship. She was a morphine addict and mentally unstable; their marriage was tumultuous. After only six months, Miriam left. Their divorce was an extremely contentious and long legal battle.

While Wright was still technically married to Miriam, he met Olgivanna, a 30-years-younger married mother and dancer from Montenegro. Once they were both divorced from their current spouses, they too married. This relationship was quite stable, and they remained together until Wright’s death.

Soon after they had moved in together in Taliesen, another fire destroyed the home. Because Wright was forever squandering his money, and needed to rebuild, he devised a way to pay the bills by having architecture interns labor at the home and work the farm while also paying tuition for the honor of studying with him, a form of indentured servitude. Wright continued to create remarkable architecture for several more decades, and died at the age of 91

Wright’s story is just too interesting to not tell. But a description of his influence on architecture and design follows. If you found his story intriguing and want to know more about his fascinating biography, let me suggest a few excellent books.

Historical Fiction:

Loving Frank, by Nancy Horan (2008). Ballantine Books.

The Women, by T. C. Boyle (2009). Penguin Books.

Non-fiction:

A Brave and Lovely Woman: Mamah Borthwick and Frank Lloyd Wright, by Mark Borthwick (2023). University of Wisconsin Press.

Death in a Prairie House, by William R.Drennan (2007). Terrace Books.

What did Frank Lloyd Wright Contribute to American Architecture and Interior Design???

Over his seven decade career, he designed an enormous quantity of buildings—almost ONE THOUSAND, but fewer than half were actually built. In the late 1800s when Wright began working for Louis Sullivan, and when he began his own practice a short time later, Americans were building homes in the VIctorian style, with box-like rooms connected by hallways.

Wright set out to develop a residential building style that was uniquely American, unlike any borrowed styles from Europe. The concept of an open floor plan—with rooms interconnected, rather than divided by walls and doors—was entirely Wright’s innovation.

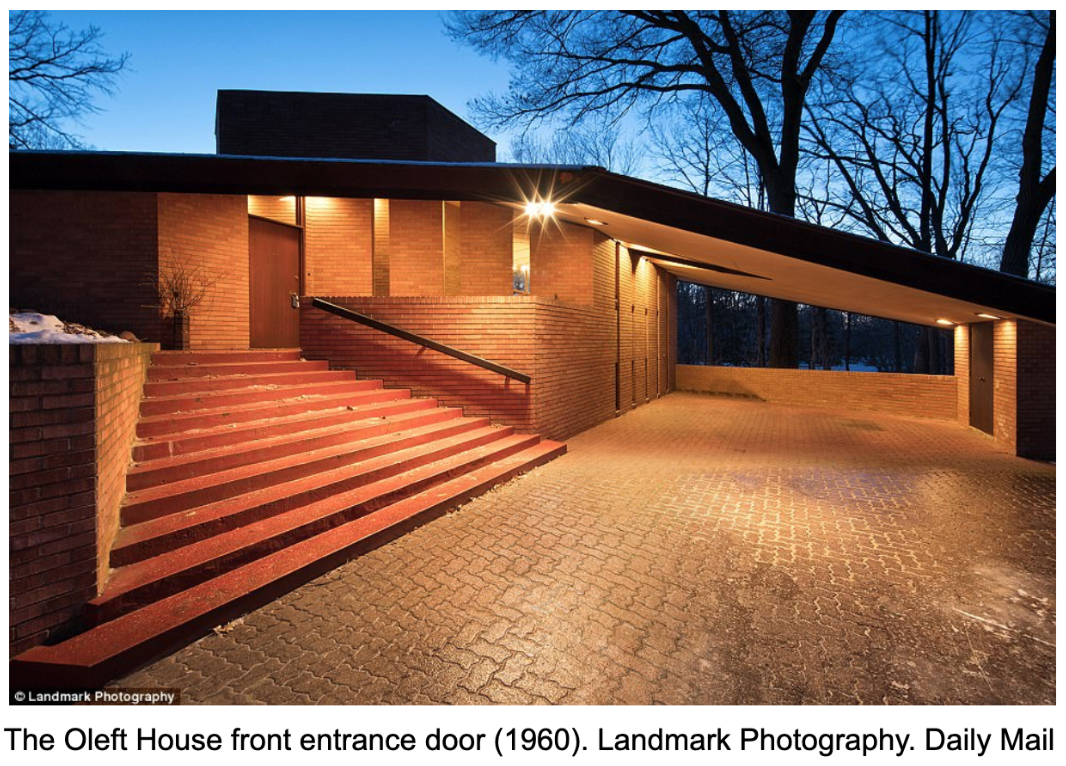

For the exteriors, he mirrored the wide-open landscape with ground-hugging, facades, low-pitched roofs, deep overhanging eaves, and use of natural materials such as wood and stone, or red brick. This style has come to be known as the Prairie School style, emulating the prairies of the upper midwest. His goal was to have the building exist in harmony with the surrounding landscape.

Wright used an interesting technique for the entry spaces of his homes. Rather than celebrating the front door, in Wright’s homes, the front entrance was often a bit hidden, understated, and covered with a low overhang. Immediately inside, the entry spaces were again somewhat confined, often with low ceilings. This was his strategy to make the entrance experience and first line-of-sight within the home noteworthy. A person enters, and senses the compression of the constricted space. But then voilà, upon venturing into the first main living space, the sense of reveal and expansion makes that space seem all the more grand.

Wright was equally interested in the interior experience. He capitalized on natural light from the out-of -doors, and used clean lines, broad surfaces, repetitions of organic and geometric shapes, and muted colors found in nature. Wright’s love of nature pushed him to carefully consider the positioning of the home to capitalize on views to the exterior. His interiors are said to possess an ethereal quality and to celebrate a profound human connection with nature. He took note of every detail, and designed not only the home, but also all of the furnishings within.

He often used a particular brownish-red color, that he called Cherokee red, which emulated earth and clay. This color was used in flooring, brick, wood tones, and upholstery. As red is the complementary color of green, these interior tones emphasized the views of the trees and grass through the windows.

In his later period, Wright experimented with textural concrete block as a building and ornamental material, which he called “textile block” and repeated shapes inspired by Japanese design and tribal motifs from Mayan architecture.

Probably Wright’s most notorious and well-known residential design is the house known as Fallingwater in Pennsylvania. While the client expected Wright to design a home with a view of the waterfall on his property, Wright instead sited the house in a way to allow a continual interaction with the waterfall from within, and included an elegant staircase down to the stream and plunge pool below.

Builders continue to use aesthetic strategies developed by Wright in homes built today. The low pitched roofs, overall horizontality, ground-hugging profile, deep overhanging eaves, brick enclosed terraces, interesting geometry, and large windows mean that the homes below would be characterized as Prairie Style, reflecting back to the influences of the great Frank Lloyd Wright.

Sources used:

Alofsin, Anthony (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright—the Lost Years, 1910–1922: A Study of Influence. University of Chicago Press.

AR Inspired Pencil. (n.d.). Prairie House Style. https://ar.inspiredpencil.com/pictures-2023/prairie-house-style

Blakeley, Kiri. (18 April, 2017). Frozen in time: Minnesota home built by renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4423470/Frank-Lloyd-Wright-built-1960-sale.html

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. (28 December, 2017). Peek inside 7 iconic Frank Lloyd Wright buildings. https://franklloydwright.org/interiors/

Glancey, Jonathan. (21 July, 2017). Frank Lloyd Wright in 5 buildings. CNN Style. https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/frank-lloyd-wright-architecture-150-years/index.html

Hoffman, Barbara. (7 June, 2017). Famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright had a dark side. New York Post.

https://nypost.com/2017/06/07/frank-lloyd-wright-was-a-house-builder-and-homewrecker/

Jaskowski, Stephan. (n.d.). Modern Prairie Style Architecture by WEST STUDIO. https://prairiearchitect.com/

Kaufmann, Edgar. (5 April, 2025). Frank Lloyd Wright: Europe and Japan. Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frank-Lloyd-Wright/Europe-and-Japan

Lippe-Mcgraw, Jordi. (11 July, 2019). A Frank Lloyd Wright home in Kansas City is headed to auction. Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/a-frank-lloyd-wright-home-in-kansas-city-is-headed-to-auction

Lockwood, C. (8 June, 1986). The houses Wright built. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/06/08/travel/the-houses-wright-built.html

New City Design. (21 April, 2015).

https://design.newcity.com/2015/04/21/restoring-unity-frank-lloyd-wrights-temple-gets-updated-for-eternity/

Optima (16 December, 2020). The legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright. https://www.optima.inc/the-legacy-of-frank-lloyd-wright/

Petridou, Christina. (25 March, 2024). Inside one of Frank Lloyd Wright's largest residences: The Westhope mansion in Oklahoma. https://www.designboom.com/architecture/frank-lloyd-wright-largest-residences-westhope-mansion-tulsa-oklahoma-04-19-2023/

Pines, Samantha, & Stewart, Jessica. (21 August, 2022). The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: 10 historic buildings by the legendary American architect. My Modern Net. https://mymodernmet.com/frank-lloyd-wright-buildings/

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Frank Lloyd Wright. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Lloyd_Wright

Wikiwand. (n.d.). Fallingwater. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Fallingwater

Wright, Amy Beth. (7 August, 2017). Seven hidden gems from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian period. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. https://franklloydwright.org/seven-hidden-gems-frank-lloyd-wrights-usonian-period/

Want to explore more issues? Here are a few favorite past editions:

Want The Design Brief® delivered straight to your inbox?

If you liked this email, be sure to sign up for The Design Brief®, our complimentary publication that gives you bite-sized lessons on all the technical interior design topics you didn’t learn (or forgot) from design school—straight from our resident interior design professor!

Looking for more? Keep reading: